Teaching activities: videos, activity ideas and information about objects

Pablo Picasso, ‘Cubist Head (Portrait of Fernande)’ (c. 1909-1910) © Succession Picasso/DACS, London 2021

- How to interpret the ideas and narratives of artists.

- Taking creative risks.

- Investigating, exploring and testing expressively.

- How to interpret the ideas of artists from different art historical genres and cultures in a political, spiritual and moral context.

- Expressive knowledge of properties of materials and processes for students to select techniques and control their outcomes.

Each resource provides a set of learning materials to support these elements:

- Close Encounter: critically examine

- Discuss: think and discuss ideas

- Create: develop their own artwork through artist-led virtual workshops or ideas and conclude with an opportunity to

- Reflect: reflect and evaluate their work

What compels us to create images of ourselves and each other?

Throughout art history we can see detailed images of human figures, depicted going about their daily lives, or sometimes formally posed in a controlled space, for example: a studio or a natural or urban environment. We usually think of a portrait as an image of a specific individual, capturing something about their personality, identity or status. More intimate portraits detail a time in someone’s life. This could be a seemingly incidental event – see Gwen John’s painting, ‘The Convalescent’; or a painting that marks an occasion such as a birthday – see the detail of the painting by the artist Millais, ‘The Twins Kate and Grace Hoare’.

As well as paintings, portraits can also be

- statues

- sculptures

- coins

- medals

- ceramic ware (pottery)

- tapestries

- prints and drawings.

These portraits may also record a particular political or historical event.

Above, we have briefly thought about identity; now let’s touch on the notion of power and control:

- Who decides what you look like in a painting?

- Who will see the painting?

- Who is NOT included in the painting?

- Who paid for the painting?

- Where is the artist in all of this?

Details

Proportionally the human face is a relatively small part of our physical self.

- What is it we seek to capture or discover in faces?

- Which part of the face do you look at to find someone’s true emotions, thoughts and responses? Is it in their eyes, mouth, forehead, eyebrows, the tilt of the head, or a facial gesture?

How can we capture these in a painting, drawing, sculpture or photo? How does the artist Millais show this in the detail from the painting, ‘The Twins Kate and Grace Hoare’?

How you could take on a different personality or identity, or an exemplary and exaggerated version of yourself?

Discuss where you might ask to be painted and the details and objects included.

- What will you wear?

- Are you involved in a ‘scene’ or posing on your own?

Discuss how many people might be ‘behind’ the portraits seen in the Fitzwilliam Museum portraits.

Think about the running of the grand houses and gardens, making the costumes and armour, preparing the food and drink…why do you think these people are unseen? Where are these people’s portraits?

Who owns your identity?

This is a topic that social media has taken to a whole new level. It’s not a new idea as many portraits throughout history were commissioned to create a particular identity.

Lucas Horenbout, ‘Henry VIII’ c. 1525

This image of a young beardless Henry VIII aged 35 is different to the image we most often think of. Why is this?

You can find out more about portrait miniature in this factsheet.

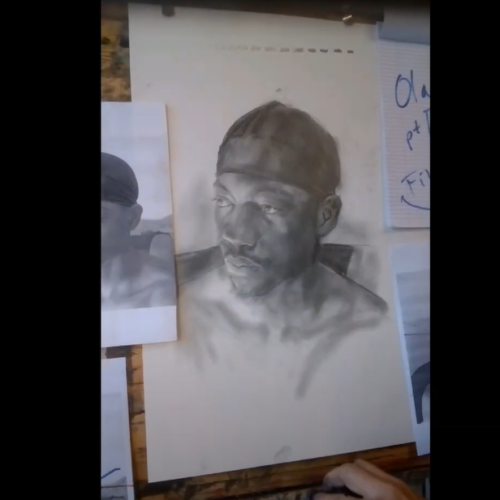

Want to learn more about realism and using pencil and graphite to create a portrait?

Follow artist John Wiltshire’s video as he takes you through some step-by-step techniques:

Materials you might need:

- Paper of your choosing but light cartridge works well

- Pencils, HB, B2, B4. Graphite stick, conte or charcoal

- Clean rag, eraser – putty rubber if you have one

We are fascinated by faces.

- Why do you think that is?

- What are we looking for when we look at other people and how is that different from when we look at ourselves?

- Of course, to see ourselves we often need to see a reflection, which is in reverse, but there are other ways that we can see ourselves – what could these be?

Explore different ways to see yourself… it might not be a reflection!

Describe how these stories tell us about ourselves.

Think about the common experiences we all share or might experience in our future selves.

How might this inform us about the decisions we take?

Think about how you might present the same person in different art historical genres (styles) and put this into a reasoned context.

Why did the artist use this style and why are you choosing to use this art genre in your own work?

Further resources

Face-to-face idea starter: ideal for Years 7-9.

How-to guide for young researchers, based on Millias’ ‘The Twins Kate and Grace Hoare’: ideal for Years 10-13.

Additional artworks

Sometimes figures depicted in artworks are models, whose identity we may or may not know. These models are often paid to play a part in particular poses and in costumes with props, perhaps showing a religious or antique scene. Occasionally these models are the artist’s friends or family, such as in the artist Ford Madox Brown’s painting, ‘The Last of England’, described here later. While these artworks capture the models’ likeness it is often not ‘about’ them. So we are going to explore the ideas around image and identity – what makes you you.

Gwen John, ‘The Convalescent’

Can you find areas that Gwen John has painted more loosely and areas where she adopts a different technique in this intimate portrait? Why has she done this?

Think about where the woman in this portrait is sitting. What is she doing and how are you involved with this narrative? The title gives us a clue as to the circumstances that this young woman currently finds herself in. How do you think reading a letter from a beloved friend might make her feel? How does this portrait make you reflect on your own experiences?

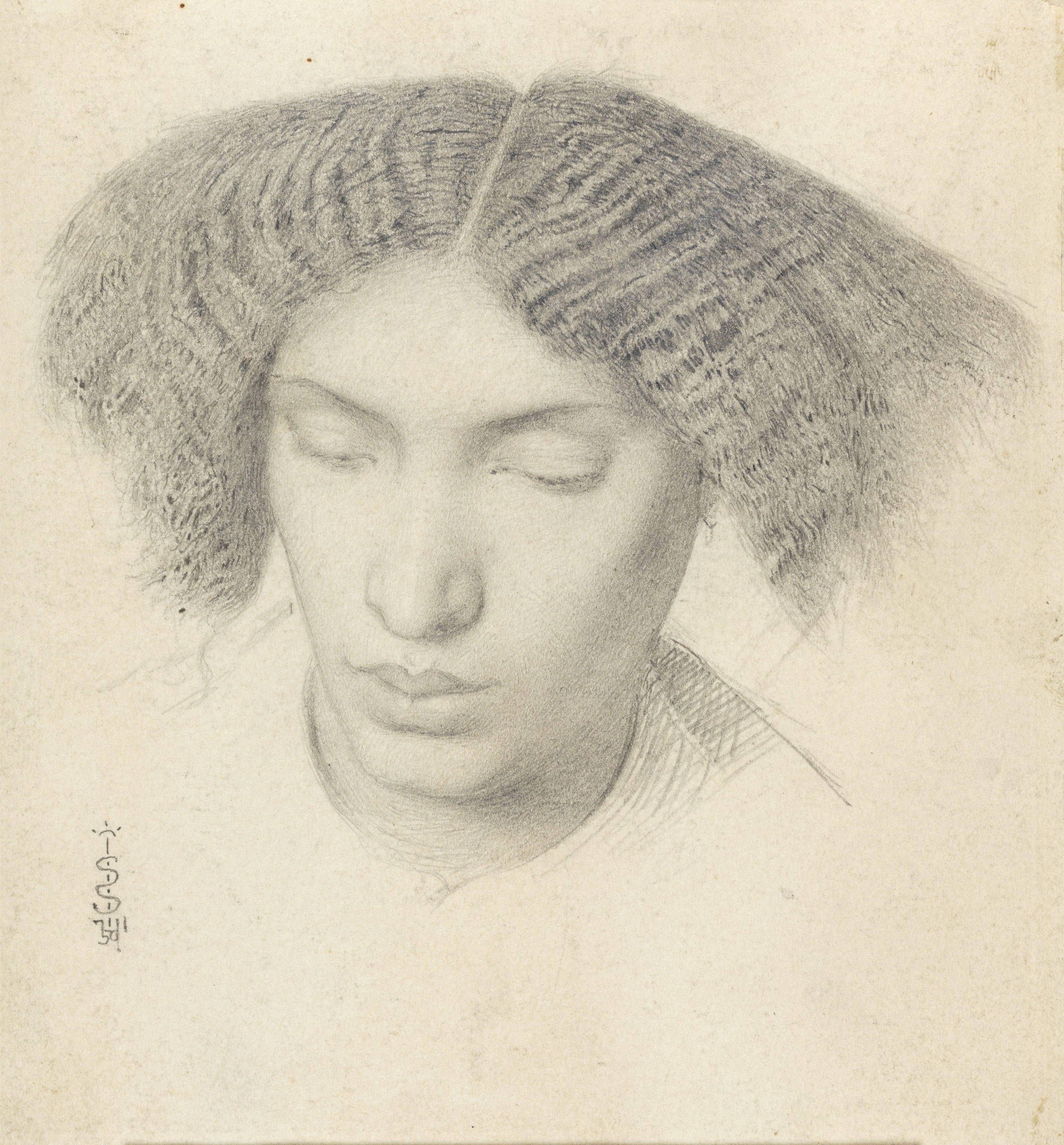

Simeon Solomon, ‘Fanny Eaton’

Artists know how to capture the subtle ranges of our expressions and there are so many examples in our collection of portraits here at the Fitzwilliam Museum. Here are a few. Try looking at these portraits when you are in different moods – how does this affect how you engage with them? You bring your own emotions, stories and experiences when you look at artworks. This is often referred to as your ‘personal narrative’.

This delicate graphite and watercolour study is of Fanny Eaton, a Jamaican woman who frequently was called on as a model for the artists in the Pre-Raphaelite group.

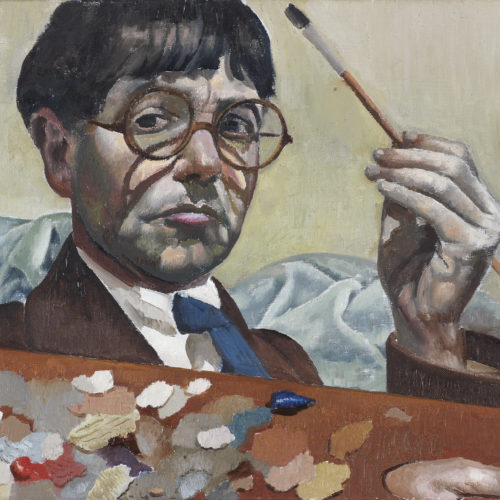

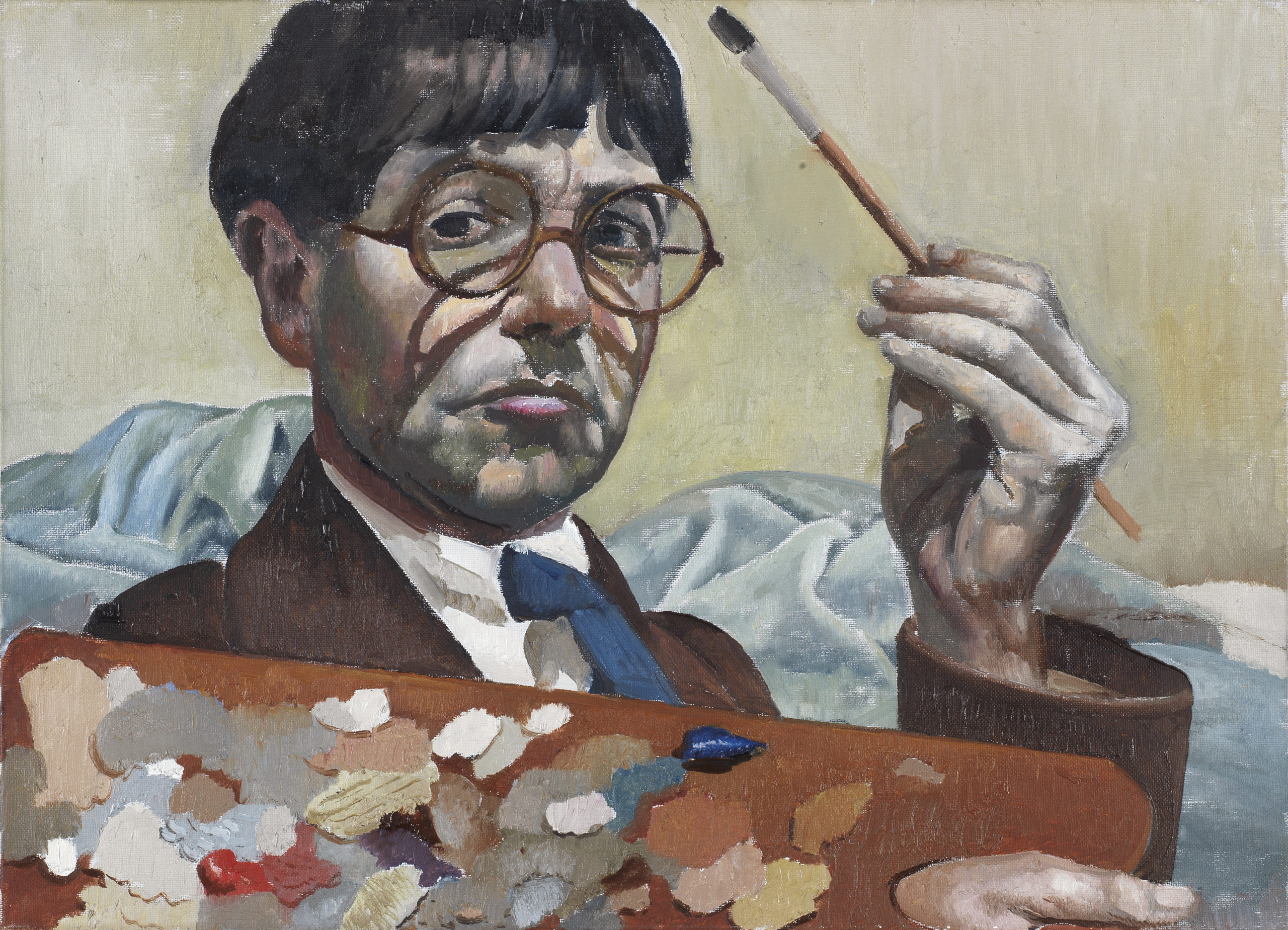

Stanley Spencer, ‘Self-Portrait’

On the canvas or paper you meet the artist’s narrative. One of the fascinations of portraits is the third narrative, that of the sitter. There is a complex blending of stories: you (the viewer), the artist, and the sitter (the subject of the painting). Compare this self-portrait by Spencer with the drawing of Fanny Eaton (above). In a self-portrait, the sitter has control of their image.

© The estate of Stanley Spencer/Bridgeman Images

Pablo Picasso, ‘Cubist Head (Portrait of Fernande)’

Picasso enjoyed experimenting with lots of different painterly techniques. Here, he is exploring cubism. At the time this was painted, at the beginning of the twentieth century, there was a fascination with mechanisation, and the construction of this painting may bring to mind an engineer’s plan or an architect’s sketch of a modern cityscape.

Can you find the portrait? Do we learn anything about Fernande?

© Succession Picasso/DACS, London 2021

Ford Madox Brown, ‘The Last of England’

Here are the artist and his wife with their tiny child beneath her red shawl. They are posing as an imaginary couple on their voyage to seek a better life overseas. This was inspired by Brown’s friend and fellow artist, Thomas Woolner, who emigrated to Australia in 1852. Why would an artist use their friends and family as their models for their paintings? If you set up a similar painting who would you choose to be your models?

Download our Portraits scheme of work as a PDF.

This resource has been designed for teaching within your classroom and is not to be used for any other purposes without the express permission of the Fitzwilliam Museum.

Some of the artists featured are in copyright and have been included with the permission of the relevant rights holders.

The copyright in all the images remains the property of The Fitzwilliam Museum, University of Cambridge.